-

Global

-

Africa

-

Asia Pacific

-

Europe

-

Latin America

-

Middle East

-

North America

- |

- BUSINESSES

- |

- Contact

- |

-

Global

-

Africa

-

Asia Pacific

-

Europe

-

Latin America

-

Middle East

-

North America

- |

- BUSINESSES

- |

- Contact

- |

You are browsing the product catalog for

You are viewing the overview and resources for

- News

- A Part of Documenting History

'A Part of Documenting History'

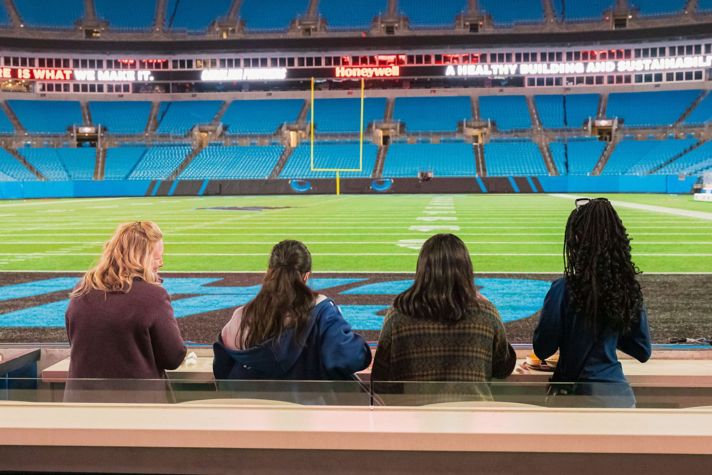

Volunteers get a first-hand look at the post-Civil War era as part of a Smithsonian transcription project

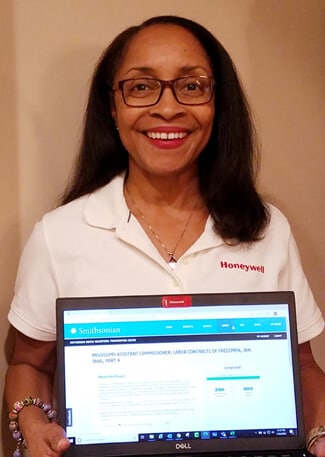

Ebony Joseph was blown away when she visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture with nine family members in Washington, D.C. before the pandemic hit.

“We were all mesmerized by everything we saw, felt, experienced and lived,” she said. “We all walked away wanting and wishing we could somehow be a part of something as big and impactful as this Smithsonian.”

During the middle of the pandemic, she learned she could do just that.

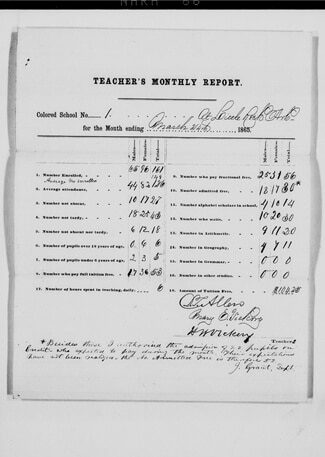

Honeywell employees, including Ebony, volunteered to transcribe The Freedmen’s Bureau Records, which document the transition of enslaved people to freedom, according to the museum’s website. The Bureau was created by Congress in 1865 to assist in the political and social reconstruction of the post-Civil War era.

Millions of records contain names of formerly enslaved individuals and refugees. Throughout February, volunteers will transcribe more records as a part of Black History Month, making this piece of history searchable and available to wider audiences.

“I am interested in learning how freed slaves, or as I have learned to call them, ‘freedom seekers,’ received land and citizenship after slavery,” Ebony said. “I wanted to learn more and be a part of documenting history.”

Here’s what other volunteers had to say about the project.

Duncan Bennett, Americas Solution Advisor Leader

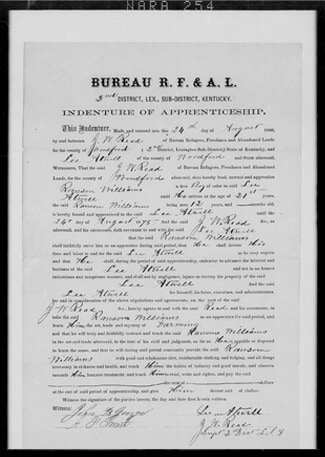

There was one record that included a father who signed a contract for himself, his children and his wife. The contract discussed how the wife was expected to do housework, including cooking and cleaning, while the father and sons were expected to do field labor. At the signature line, each person placed their ‘mark’ which was always an X since most slaves were not allowed to be taught to read and write. I am still struck by the great opportunity we all have for learning today in contrast to the restrictions placed on so many in the past. And I am grateful for their sacrifice and the sacrifices of so many others to afford us the luxuries we accept as rights today.

Sheila Budd, Lead Commercial Excellence Specialist

I was immediately moved by the beauty of the cursive penmanship, which put me in touch with the humanity of the circumstance. As I transcribed the labor contracts, I felt an awareness of their sense of purpose and being valued for receiving payment for work that had once been done under the rule of slavery.

Contessa L. Dorsey, Engineering Principal

What stood out to me was the level of scrutiny required in reviewing the fine, longstanding documents. As an African American that yearns to know more about my ancestries’ impact and history; I appreciated the consideration and attention to detail utilized to ensure the content was accurate. There were several layers of verification and validation in their review process.

Karen Anderson, Sr. Advanced Engineering Support Specialist

The story of the Freedman’s Bureau was something I knew little about before delving into this project. I loved being deep in it – reading what was crucial to people and their livelihoods at that period of reconstruction, 1865-1872. It was enlightening to read about the impact of war, freed slaves and how the government assisted in the allocation of land.

Aijone Austin, Systems Engineer I

The most impactful thing about what I had to decode was understanding the value of African Americans compared to now. We like to believe in history these events occurred long ago, however, the documents gave me an understanding to just how recent these times were for us as a culture.

Josephine Elia, Sr. Advanced Applications System Sales Engineer

The records I transcribed were labor contracts between plantation owners and the laborers/freed slaves. The most heartbreaking part about reading these documents was the fact that the demands required of the plantation owners were so minimal, and yet they had to be written explicitly on official documents. For example, they were to provide the laborers with “good and sufficient” clothing, food, and living quarters, medical attendance and “kind and humane treatment.” In one case, a woman laborer simply wanted her enough time to make clothes for her two daughters and herself. Living in 2021, we know of the history of slavery from a distance, allowing us to distance ourselves emotionally from what happened. But being face-to-face with these documents brought me a little closer to that reality. Reading and writing the names of the freed people, the names of their children, the things they cared most to include in the contract, helped me see the humanity in these individuals that historically had been denied.

Sally Garza, Global Lead for Process Equipment

The true story of the documents are told in the underlying details. Analyzing the character of the font, the type of ink used in that particular era, the angle of the author’s hand, the weight of the instrument in writing – all of the elements within create a story. Analyzing and transcribing these records provided me with an understanding and a true appreciation for the struggle endured by so many African Americans.

Jane Sherburne, Senior Advanced Software Engineer

I was transcribing documents that were the contracts for Freedmen between them and their former owners. There was a standard paragraph that stated the newly freedmen were to get 10% of the goods, products and land of the plantation or farm, to be fed and clothed and provided medical care. Many of the contracts were handwritten in elaborate or fanciful script while some were typewritten. These contracts also had a handwritten section filled in by the plantation or farm owner. The script here was very often a much more crude handwriting. This section might describe the particular crops that were already shared, clothing already provided and planned to be provided, or it might be used to state specific terms agreed between the parties.

Rob Slone, Chief Technology Officer, Honeywell Advanced Materials

The small, very human, moments of everyday life captured in the text being transcribed stood out for me. There was one page from the post-Civil War South in which an elderly African American woman was seeking help from the local federal troops to procure flour and sugar to help feed her family. The soldiers did pass the woman’s note along and deliver the food ingredients requested, but they could not spare any coffee at that time. Seeing the soldiers help and share what they had was encouraging.

Mark A. Woods, Inventory Clerk

I verified transcriptions and transcribed ledgers and manifests. I plan to get my mother, who is in her 80s, and my three teenage daughters involved. I want to have my family see actual history and be part of it. The thing that hits me the most is knowing that things can get better. Seeing a part of my birthright being nothing more than commodities evaluate themselves from one generation to the next gives me hope for myself and my children. Just looking at a document that verified that someone was more than property and seeing my own life is humbling. With everything that is going on now, I can see there’s a chance for the future.

Copyright © 2025 Honeywell International Inc.